Without and Within: Essays on Territory and the Interior

Book review published in: Architectural Research Quarterly, volume 11 number 2, 2007

The echoing well that has been dug by urban scientist after the work of Manfredo Tafuri reverberates with a peculiar variety of new words and phrases lately. The ‘generic city’ term coined by Rem Koolhaas comes to mind. For younger generations of architects and urbanists the city is a self-referential and hard-to-control monster again, just like it was at the beginning of the 20th century. Artist and teacher Mark Pimlott has added a new chapter to the history of the city that appears to just happen to us, in which the claim on any form ‘authentic’ architectural expression seems to have gone and serious hope for public masterplanning is lost. His book Without and Within: Essays on Territory and the Interior is a collection of essays on territory and interior and investigates controlled megastructures, such spaces and places as shopping malls, supermarkets, pedestrian subways, airport terminals and even recent art museum designs which are based on the imposition of desirable human conduct, economic conditions, imagery, fantasy and even climate within an architecture that has become so familiar to us that we do not recognise its deliberate weak nature anymore.

The echoing well that has been dug by urban scientist after the work of Manfredo Tafuri reverberates with a peculiar variety of new words and phrases lately. The ‘generic city’ term coined by Rem Koolhaas comes to mind. For younger generations of architects and urbanists the city is a self-referential and hard-to-control monster again, just like it was at the beginning of the 20th century. Artist and teacher Mark Pimlott has added a new chapter to the history of the city that appears to just happen to us, in which the claim on any form ‘authentic’ architectural expression seems to have gone and serious hope for public masterplanning is lost. His book Without and Within: Essays on Territory and the Interior is a collection of essays on territory and interior and investigates controlled megastructures, such spaces and places as shopping malls, supermarkets, pedestrian subways, airport terminals and even recent art museum designs which are based on the imposition of desirable human conduct, economic conditions, imagery, fantasy and even climate within an architecture that has become so familiar to us that we do not recognise its deliberate weak nature anymore.

‘American and European ideas about space and place are entirely different: the former is forged out of system-based strategies superimposed on the World (Pimlott reserves a capital W for our planet, HvdH), and the latter from a meeting with the World, in which resides the possibility of encounter with otherness’, Pimlott asserts in the introduction to his book. Today’s public urban spaces are guarded, air-conditioned and carefully supplied with items triggering our desires and dreams. Its investigation is slippery territory, because these edifices defy any architectonic classification. By no means exclusively American anymore, such environments form a distinct phenomenon, but paradoxically share a vague set of typological, tectonic and formal properties. Indeed, the word environment is more apt than the word edifice.

Pimlott makes his case with texts and images. The essays present a more or less continuous story line in which a number of unrelated scale jumps within the planning of the American territory are manifest. The first takes place between Jefferson’s 1785 Land Ordinance and the 1862 Homestead Act. In this period of time the European fashion of planning defined places on the basis of historic examples moved towards a frontier ideology in which space was regarded as infinite and empty, only waiting for colonisation by the new American entrepreneur. A second shift in scale emerged when the outskirt developed into vast production fields of consumers that were of crucial importance to the economy of America. The growth of the gridded urbanised American hinterland after the second World War created a shift in consumerism. The distinction between city and hinterland blurred, stimulating an increase and spread of the outlets of consumer goods. The shopping mall was born. The first ones were had their own formal repertoire, freely configured and connected to the highway interfaced by enormous parking fields. A third scale jump is represented by the congestion of the old city centres. Here, in the 70-ies, the ground floor atrium of the American skyscraper was introduced in order to compensate the enormous physical impact of the edifice itself and was regarded as beneficial to the city centre inhabitant. Its public (or better: quasi-public) status was to stimulate traditional urban activities back into the city centre. The City Corp Centre skyscraper sheltered an atrium as well as a church, punctuated by worship, cafes and lunchtime concerts. A traditional farmers market was transplanted into the New York metropolis.

At this point in the book the narrative circle closes. The farmers market was not realised in its original shapes, but in those in which suburban development had recast them. The urban atrium as an Edenic environment filtered through the imagination of suburbia. It is worth to quote Pimlott at length: ‘That promised urban centre was achieved by the suburbanisation- through interiorisation- of downtowns in key, representative areas; the displacement of commercial enterprises, originally associated with the city centre, to the suburban regions, and their distribution at nodes of and expanded grid (following a regional rather than urban scale); and the concomitant relocation of corporate headquarters from the urban centres in favour of the motorway-crossed regions. The result was a completely dispersed urban experience, in which qualities of the city found themselves scattered throughout the extra-urban regions and vice versa.’

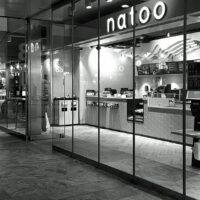

Upon this analysis Pimlott builds a critique of a number of recent megastructural environments in the world of high architecture: the Economist Building by the Smithsons, the Louvre extension by Pei, the Kunsthal and Seattle Public Library by OMA. The character of the book changes from somewhat academic and studied, but always illustrated with a careful selection of supporting images, to more natural and fluid. Footnotes do not disappear altogether, but lose their immediate relevance. Moreover, the text is accompanied by a range of photographs that are made by the author. Printed on large format, these images suggestively and autonomously contribute to the written contents of the book, even more so than the images in the previous essays.

Back to the post-Tafuri echoing well. Koolhaas’ diagnosis of the city has been liberating for a whole generation of Dutch designers by generating their space to design: Dutch turbo modernism consciously celebrates capitalist decadence. Tafuri’s Italian school has often been accused of being negative, fatalistic or even paralyzing. With all his reservation to his object of study Pimlott seems to be more sympathetic to the Italian camp. Without and within does not celebrate of a current state of affairs, but instead presents a variety of means to understand the origins and the impact of the mall and the airfield better. However, the real precedents for this book are not in the scientific realm, they are found in the art world. The texts have different focuses and characters. They might be historic surveys, interpretations of imagery, architectonic observations, analyses, comments and critiques and address both low and high architectural design. Crucial, and perhaps underestimated by the author and his editors, are the dreamy black and white photographs of the artist Mark Pimlott. These shots put us back in the reality of the world. Pictures and words relate to day-to-day experiences, but also to our intellectualisation of those. Pimlott succeeds to keep the study more or less within the architectonic discourse. Yet his differentiated scrutiny is more akin to the work of, say, Dan Graham than Tafuri’s. It is an adequate response to the architectonic vagueness of his object of study. Not offering a clear-cut thesis or conclusion, it is food for thought, a substantial book, a Book.

Back to the post-Tafuri echoing well. Koolhaas’ diagnosis of the city has been liberating for a whole generation of Dutch designers by generating their space to design: Dutch turbo modernism consciously celebrates capitalist decadence. Tafuri’s Italian school has often been accused of being negative, fatalistic or even paralyzing. With all his reservation to his object of study Pimlott seems to be more sympathetic to the Italian camp. Without and within does not celebrate of a current state of affairs, but instead presents a variety of means to understand the origins and the impact of the mall and the airfield better. However, the real precedents for this book are not in the scientific realm, they are found in the art world. The texts have different focuses and characters. They might be historic surveys, interpretations of imagery, architectonic observations, analyses, comments and critiques and address both low and high architectural design. Crucial, and perhaps underestimated by the author and his editors, are the dreamy black and white photographs of the artist Mark Pimlott. These shots put us back in the reality of the world. Pictures and words relate to day-to-day experiences, but also to our intellectualisation of those. Pimlott succeeds to keep the study more or less within the architectonic discourse. Yet his differentiated scrutiny is more akin to the work of, say, Dan Graham than Tafuri’s. It is an adequate response to the architectonic vagueness of his object of study. Not offering a clear-cut thesis or conclusion, it is food for thought, a substantial book, a Book.