Think Differently

Book review Cameron McEwan, Analogical City, published in Dutch on: website Archined, 2024

Recently, the Scottish educator and researcher Cameron McEwan published a book on the idea of the Analogical city launched by architect Aldo Rossi (1931-1997). In the Netherlands, Rossi is known for the Dutch editions of his most important books, The Architecture of the City (2002) and Scientific Autobiography (1994), as well as for the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht (1995), which he designed, and the retrospective exhibition of his graphic work at that museum (2015). Even with such a quick introduction, much has been said about Rossi’s oeuvre. Not only was it extensive, it was multifaceted.

Rossi was a neo-rationalist, who designed, built, wrote, theorized, taught, drew and painted. Not infrequently, that scope and multiplicity prompted schematic interpretations. One hears that The Architecture of the City represents theory in Rossi’s legacy, while Scientific Autobiography represents practice. Thus he would never have matched the architectural power of his white-painted residential buildings and schools in North Italy, also not – or even not – in Maastricht. And so his poetic, graphic work would contradict, or mystify, his rationalist writings.

The analogue city is eminently difficult to capture in such schematic representations of things (McEwan, by the way, is considerably more thorough in exploring these clichés and provides other, academic examples). Oddly enough, Rossi himself remained vague about his concept of the analog city. So a study of this concept is welcome, especially when conducted by an author at a distance from the architectural debate in Italy half a century ago. McEwan’s actualization of Rossi’s work does not stand alone. Consider, for example, The Urban Fact, A Reference Book on Aldo Rossi by Jelena Pančevac & Kersten Geers (2021) and Henk Engels’ dissertation Autonome architectuur en de stad: Ontwerp en onderzoek in het onderwijs van La Tendenza (Autonomous Architecture and the City: Design and Research in the Teaching of La Tendenza, 2023).

McEwan does not make things easy for his readers. He assumes that they have considerable prior knowledge of Rossi’s work and are also familiar with the then-current vocabulary of the neo-rationalist circles surrounding Rossi. McEwan conceives of the analogy as an expression of ‘thinking differently’, as an act of rebellion that is oppositional and critical. Rossi’s analogy is in dialogue with architectural history and aims to be a hinge between past and future. On the one hand, the analogy does not offer the design research that is served up ready-made for implementation; on the other hand, the analog city is not a non-committal dream or a utopia. It is, according to McEwan, a vision of a potential other reality. With his analog city, Rossi does not resign himself to the notion that between the dream in which everything is possible and the restraining forces of the construction economy, there is only the toiling of everyday design practice.

The analogue city is imaginary. Rossi visualized its architecture through drawings. By definition, these are not documents that synthesize practical requirements into a executable design, but constitute a site of another reality. The drawings are not merely technique, but constitute themselves an architectural territory. McEwan puts it this way: ‘… the analogical city holds an ambiguous position within Rossi’s thought. The analogical city is not a fully developed theory nor is it only an “intuitive,” “poetic,” or purely formal practice, as some critics propose. It is my position that the analogical city is poetic and political, and it always refers beyond itself towards a collective project of the city (…)’.

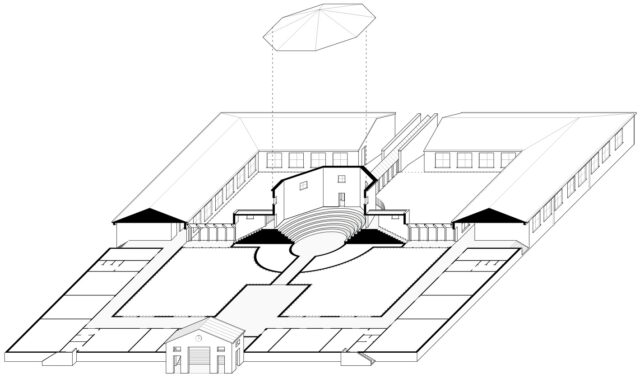

McEwan writes the history of the concepts and ideas that led to Rossi’s concept of the analogue city. The jargon of Rossi’s time undoubtedly needs interpretation today. McEwan arrives at a lexicon that includes such terms as: city as a text, type, collective memory, analogical rationalism, correspondences, capriccio, analogical–formal operation, act of refusal, unconscious thought, dialectical imagination, repetition, destructive character, and déjà vu. Take the notion of type. Rossi viewed type as a perfectly pictureless starting point for design. In a manner of speaking, type is a structure without properties. Only after concrete properties have been assigned, that is, after the design of geometry, proportions, constructions and materials is ready, according to Rossi, is there a building. In his own buildings, that process can be recognized in the recurring use of the comb type. That in itself featureless and repeatable fact charges Rossi, for example, in the aforementioned Bonnefantenmuseum through the introduction of a museological long staircase in the central wing, the dome on the River Meuse and the quasi-industrial treatment of the brick facades. Behind each building are common characteristics that are collectively understood. The concrete manifestation of the building through the design work of an individual positions the type in space and time.

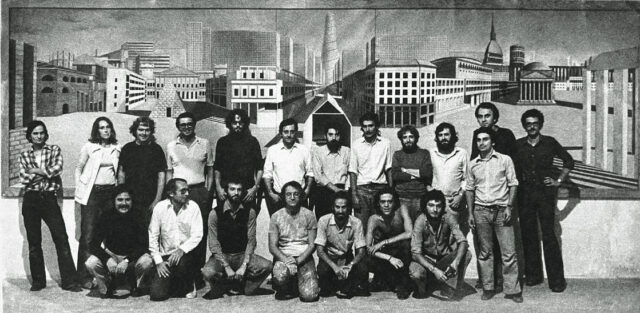

The rationalist circles around Rossi shared not only a lexicon but also a canon, for example, of historical capriccios. An important tenet of this constitutes the capriccio painted by Giovanni Antonio Canal (Canaletto) of the Grand Canal near the Rialto Bridge in Venice. The painter replaced a number of buildings with designs for Vicenza, all by Andrea Palladio. McEwan asserts that the painting does not represent Venice because the buildings Canaletto paints are from Vicenza, but that it also does not represent Vicenza because the depiction is recognizable as the Rialto in Venice. The painting depicts neither Venice nor Vicenza. Instead, Canaletto presents a counter-project, in which the analogical city is a critical act of negation of the existing city. It is a depiction of the city beyond the real city, beyond the status quo. Also part of that same rationalist canon are Giovanni Battista Piranesi‘s etchings on which fragments of ancient Rome formed an imaginary new city and La città analoga, a seven-meter-long painting by Arduino Cantàfora from 1973. The latter painting presented a cityscape with diverse structures designed by Adolf Loos, Peter Behrens, Aldo Rossi alongside a series of unnamed Roman architects. La città analoga is a vision in which reality and the possible converge in a single image.

At length, McEwan analyses the collage created by Aldo Rossi himself. In Analogous City: Panel, he similarly combines architectural fragments of diverse origins and achieves an image that is at once familiar through memories of cities and yet strange through the rearrangement of those fragments. Such capriccios show that the history of architecture is commonplace. McEwan’s subtext is that history belongs to everyone and that anyone can appropriate and re-experience architecture.

One of McEwan’s merits with this book is that he demystifies the notion of the analogue city and demonstrates vividly how analogy offered Rossi the space to ‘think differently’. What exactly needed to be thought of differently is less well revealed, and here the assumption of extensive prior knowledge of the rationalist debate surrounding Rossi may be the cause of regret. After all, in the 1960s and 1970s, the historic city had become vulnerable to functionalist City formation. For this reason alone, the products of ‘thinking differently’ in the analogical city and Rossi’s rationalist meticulous studies of the concrete historical city are closely intertwined and result in a countermovement. Rossi’s rational city itself was the result of ‘different’ (or at least critical) thinking, because it provided a sharp discontinuity with modernist rhetoric. The rediscovery of the historic city and the subsequent neo-rationalist study by Rossi and his contemporaries provided the architectural language for this. Both shared the same activist engagement.

In passing, McEwan shows what changed after Rossi’s heyday. He writes: ‘The idea of authorship has in recent decades been associated with the author-architect of “iconic’’ architecture. This “icon culture” has destroyed the legitimacy of authorship and demeaned the architect, reduced to a “personality” within the present celebrity driven ethos. On the contrary I wish to reassert authorship as a type of critical agency and a responsibility of architecture towards the city, collective life, and democratic society.’ McEwan argues for a resistant authorship of the architect who wants to be in dialogue with common historical and political realities.

However, that is not the only thing that has changed after Rossi. ‘Today, institutions are no longer clearly bounded, but organized within global networks, logistical territories, and expanding peripheries. Individuals are on call. Work is dispersed in diverse and varied places from the classroom to the care room, the call centre to the coffee shop, and now the Zoom room. The city itself is what Negri has called a “diffuse factory”’. Similarly, the architect has become an on-call worker. Competition briefs in recent decades, for example, have taken on the character of a call for tenders, of specifications. They are no longer forums for ideation or critical action. Theorisation on the overlap of practice, research, education and public manifestation is a thing of the past. What now passes for design theory are not infrequently expressions of architects as part of their PR. Consider the stream of publications on the theme of Adaptive Re-use, which link the sustainability issue to the signature or alleged specific professional qualities of individual architects, but which invariably put the architectural can-do first. Architecture = action + turnover. Not only do research and analysis fall out of the scope, but also the ability to make do with what is already there without intervention. The architect too has become an employee of Negri’s diffuse urban factory.

McEwan discerns in contemporary activist movements such as the Gillets Jaunes, Occupy and Black Lives Matter a desire for an alternative to ‘the spectacle of consumer capitalism, nationalism, the practices of domination and the exploitation of social and natural forces brought about by neoliberalism.’ The question is where and how this unrest affects architecture and where, if at all, the critical potential of the architectural profession lies. McEwan makes it implicitly clear that ‘thinking differently’ is meaningless without a rational systems critique that compares the physical city and the social and economic city. In Rossi’s case, although building practice and and thinking differently about the analogous city were separate domains, they maintained a reciprocal relationship. Whichever way you look at it, and however explicable by the opposition to City formation, Rossi was selective in his engagement with the ancient city. That, too, has changed. The ancient city is doing fine these days. Amsterdam and Venice are succumbing to their own fame. McEwan’s observations are an encouragement to understand the new diffuse city factory as architecture.

Something is in the air. Architecture students are becoming increasingly aware of that reality. These include the periphery, urban sprawl, reconstruction architecture. The Eurocentrist historiography of architecture is passé. My Iraqi students speak self-consciously of Mesopotamia as the cradle of architecture. In this situation, the analogue city has relevance. The wait is for a Rossian genius who finds space to make the collage of an analogue city in which exotic sources reconcile with the international reconstruction city and at the same time is able to fathom and comment on the contemporary diffuse urban factory.

Cameron McEwan, Analogical City

punctum books, Earth, Milky Way, 2024

ISBN-13: 978-1-68571-122-1 (print)

ISBN-13: 978-1-68571-123-8 (ePDF)