Haus im Park

Design review sheltered housing designed by Modersohn Freiesleben, published in De Architect #4 2024

In Berlin Pankow, the architectural office of Johannes Modersohn and Antje Freiesleben (MoFrei) realised a building for assisted living that stands out for its unique lightweight tectonic and the well-thought-out integration of the housing programme for disabled residents. The result is inextricably linked to the unique collaboration of the women who developed and designed the building.

In Berlin Pankow, the architectural office of Johannes Modersohn and Antje Freiesleben (MoFrei) realised a building for assisted living that stands out for its unique lightweight tectonic and the well-thought-out integration of the housing programme for disabled residents. The result is inextricably linked to the unique collaboration of the women who developed and designed the building.

Whereas the German word for client is Bauherr, the Sozialdienst katholischer Frauen Berlin was represented by two women who emphatically presented themselves as Baufrauen. Unlike what is customary in Germany, MoFrei was awarded the contract without a prior competition or job interviews of architects. This heralded a collaboration that was less about competition, authority or mandate than about achieving common objectives through mutual understanding, self-discipline and responsible professional behaviour. With two female project architects, Antje Freiesleben was responsible on behalf of MoFrei for the architectural design, but also for the entire commissioning of the various consultants and the architectural and installation subcontractors. In Germany, it is not a given that the so-called Bauleitung is assigned to the designer of the building. However, it meant that MoFrei performed a large part of the tasks that the main contractor in the Netherlands would have performed, namely contracting, managing and monitoring the subcontractors. The office therefore had an unusually large mandate. Obviously, this level of control does not come without knowledge, skill and a responsible attitude.

Freiesleben showed herself to be very aware of her role in controlling costs and quality, although this would not be apparent from the building’s design. The homes are designed as freely shaped villa in a spacious garden. The ground floor contains communal areas and space for daytime activities. The three upper floors contain the apartments. Pairs of residents live in each apartment and share a living room and kitchen. Each resident has a private bedroom and bathroom. The bathrooms are located along the facade and have large windows. Unlike the hotel-like design with bathrooms along the corridor, the homes are positioned widthways along the façade and benefit from an unusually large amount of daylight. The bathroom is a true part of the domestic domain.

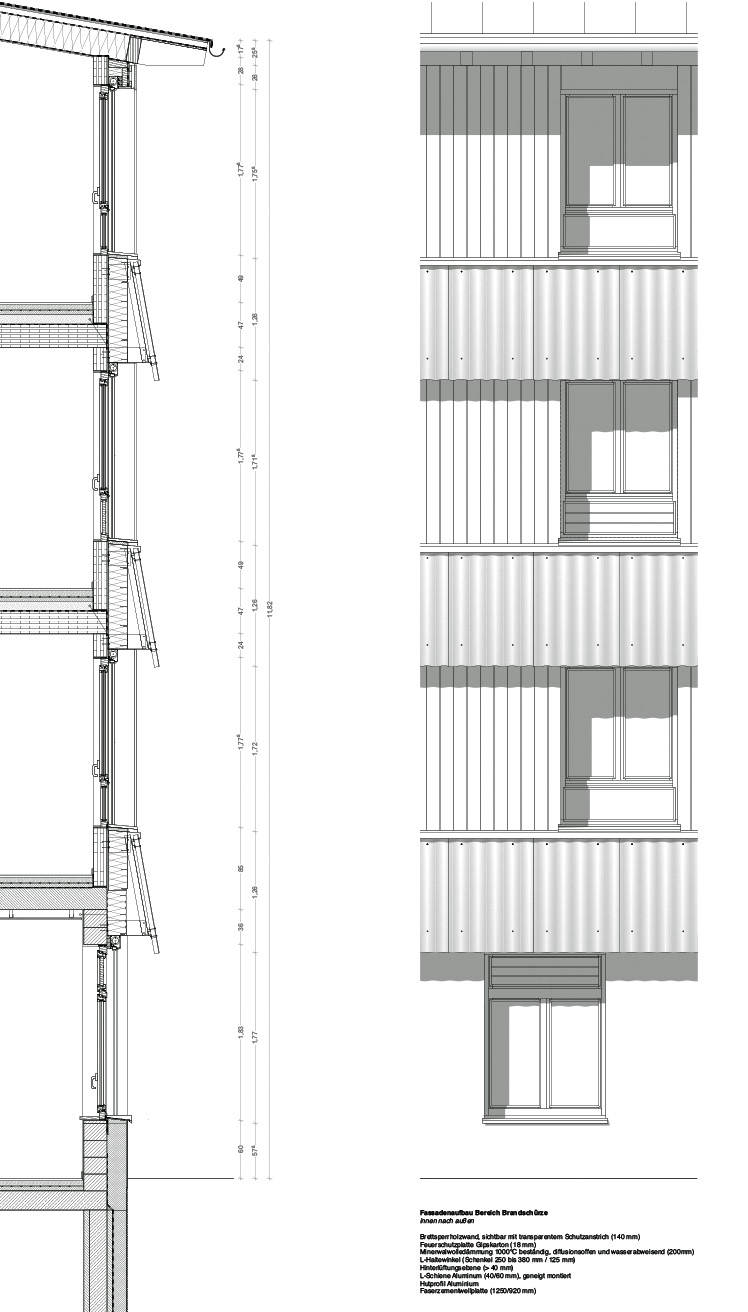

A construction method using prefabricated solid timber panels was chosen. Only the lift and stairwell cores and the ground floor are made of stony materials. The ground floor façades are finished with exterior wall insulation and green plaster. The main material of the façades and the overhanging eaves is red painted timber. The efficiency of timber construction is partly dependent on lightweight facade finishes. Freiesleben made two tectonic observations. First of all, sheet materials tend to deprive the facade of the suggestion of heaviness and solidity, as a result of which wooden buildings tend to appear ‘flabby’ and abstract. Furthermore, these light façade constructions are unsuitable for limiting the transmission of fire. For that reason, slightly tilted corrugated sheets have been added to the wooden façades, which simultaneously serve as a parapet and as a barrier to limit the transmission of fire. Like ruffles on a dress, the parapets enhance the free form of the villa and contribute to the sensation of plasticity and solidity. The materials are assertive components of the architectural composition, particularly due to their colourfulness.

The qualities are evident. And of course these choices cost money. The construction process was therefore a high-stakes game, which could be played effectively thanks in part to MoFrei’s self-discipline. All the materials and colours used are from the catalogue. The corrugated iron sheets are processed in standard lengths and widths, minimising waste and sawing losses.

That attitude of the office is reflected in the interiors. The requirements that residents with disabilities have for their living environment have been met casually. With the knowledge that the larger whole of the architectural design was sound, the architects looked for savings where they could. For example, the stairwells were done in two shades of standard grey. At the lift exit on each floor, there are exactly as many dark floor tiles as there are floor levels, an unobtrusive gesture for visually or intellectually impaired users of the building. The first and last steps contrast with the light main tone due to their dark hue, as do the tiles that mark corners, passageways, entrance mats and the like. These are solutions that do not cost a tiler any money, but which do require careful preparation and the ability to improvise on the part of the architect cum Bauleiter. ‘It’s cooking with what you have’, in the words of Freiesleben. There are architects who use grander words for their brainchildren.

That attitude of the office is reflected in the interiors. The requirements that residents with disabilities have for their living environment have been met casually. With the knowledge that the larger whole of the architectural design was sound, the architects looked for savings where they could. For example, the stairwells were done in two shades of standard grey. At the lift exit on each floor, there are exactly as many dark floor tiles as there are floor levels, an unobtrusive gesture for visually or intellectually impaired users of the building. The first and last steps contrast with the light main tone due to their dark hue, as do the tiles that mark corners, passageways, entrance mats and the like. These are solutions that do not cost a tiler any money, but which do require careful preparation and the ability to improvise on the part of the architect cum Bauleiter. ‘It’s cooking with what you have’, in the words of Freiesleben. There are architects who use grander words for their brainchildren.

Nevertheless, the ruffle tectonic is an important innovation in the lightweight architecture that sustainable building requires. In that respect, the roots of MoFrei are undeniably in the critical reconstruction after the reunification of Berlin, led by the Senatsbaudirektor Hans Stimmann and the patronage of the architect Hans Kollhoff. It was an urban programme centred on the historic stone city. It resulted in impressive concrete and natural stone buildings. Like all activism, the critical reconstruction carried a certain doggedness: in those years it was not only possible to measure up as an architect to greats like Karl Friedrich Schinkel, but to get the critical reconstruction off the ground that culture war was also necessary to.[i] As a young representative of that movement, MoFrei leaves that doggedness far behind in 2024. The cladding tectonics of the park house in Pankow are both flawless and light-footed.

The design is based on overview, patience, professionalism, humour and a great deal of experience. By orienting itself to the functional, architectural, technical and financial context, it largely speaks for itself. However, these observations do not do justice to the history of the park house. Only after some prodding does Antje Freiesleben admit that she had been waiting 30 years for the reciprocal approach of the Baufrauen. In the authoritarian male-dominated world of housing construction, she often felt like she was being backed into a corner.

The soft skills of the Baufrauen and the architects they employed were decisive in the realisation of a tectonic experiment in stringent housing construction. The history of the creation of this masterpiece in Pankow is a lesson for clients and contractors in housing construction.

[i] See also: Hans van der Heijden, Realistic construction, proposals for Berlin / Realistische Konstruktion, Vorschläge für Berlinhttps://hvdha.com/en/wirklichkeit-reality/, in: Johannes Modersohn, Antje Freiesleben (ed.), Wirklichkeit / Reality: Park Books, Zurich 2020

[i] See also: Hans van der Heijden, Realistic construction, proposals for Berlin / Realistische Konstruktion, Vorschläge für Berlin, in: Johannes Modersohn, Antje Freiesleben (ed.), Wirklichkeit / Reality: Park Books, Zurich 2020