Zivilarchitektur

Published as Timmermansoog column on: website Architectenweb, 2018

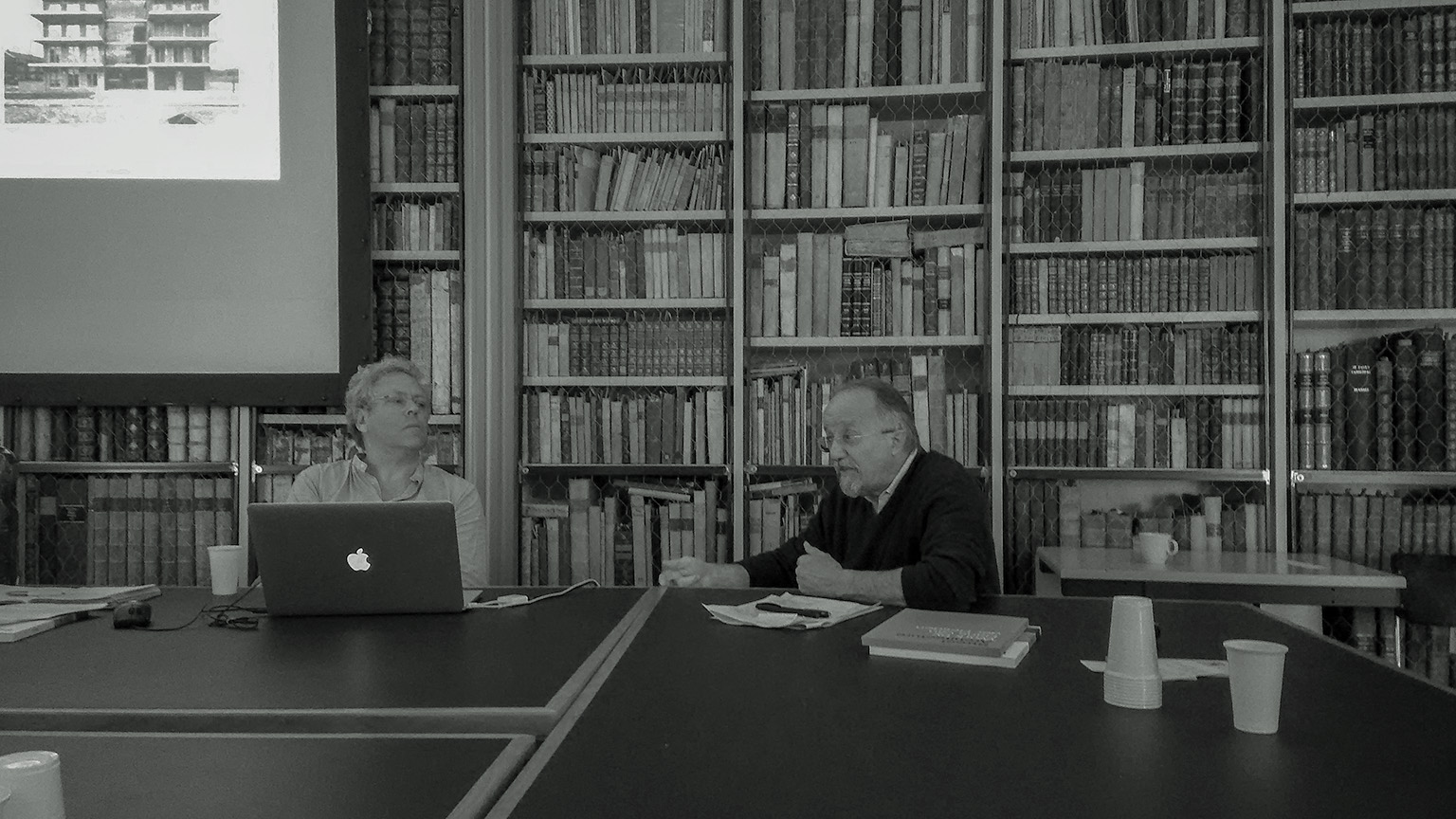

The architectural historian Werner Oechslin organized a conference on the theme of Zivilarchitektur a few weeks ago. The gathering took place in Werner’s library in Einsiedeln, Switzerland. Surrounded by an impressive collection of antique books, an international group of architects and historians discussed the history and topicality of Zivilarchitektur. That term should not be confused with something like ‘civil engineering’. Rather, it refers to ‘civic architecture’; all public and private tasks in architectural history that were distinct from military or naval architecture. Werner Oechslin questioned nothing less than the public significance of architecture and its intelligibility. That discussion is of all times, it turned out.

The architectural historian Werner Oechslin organized a conference on the theme of Zivilarchitektur a few weeks ago. The gathering took place in Werner’s library in Einsiedeln, Switzerland. Surrounded by an impressive collection of antique books, an international group of architects and historians discussed the history and topicality of Zivilarchitektur. That term should not be confused with something like ‘civil engineering’. Rather, it refers to ‘civic architecture’; all public and private tasks in architectural history that were distinct from military or naval architecture. Werner Oechslin questioned nothing less than the public significance of architecture and its intelligibility. That discussion is of all times, it turned out.

For example, German art historian Brigitte Sölch talked about the evolution of judicial building architecture. In the Venetian Palazzo Ducale from 1424, suspects and convicts were displayed to the public on the first floor of the building. Its deterrent effect took precedence over the functionality of justice, which took place on the first floor. The ‘Vierschaar’ in Amsterdam’s 1655 City Hall had a comparable place next to the entrance on the first floor. At the same time, the interior of the courtroom was dramatized. In a completely white marble hall, the verdict was pronounced from above, from a window, all for the education and entertainment of the public.

In the nineteenth century, the legal profession would professionalize. Notions such as impartiality and expertise of the law, and especially the postponement of judgment until guilt was proven, ensured that the courthouse was no longer assigned a didactic or deterrent function, but rather had to convey detachment and professionalism. The public exterior staircase and a classical architectural idiom were means of achieving this.

Brigitte Sölch demonstrated how in recent courthouses the concept of transparency has taken on an allegorical meaning. It stands for transparency in law, but also for neutrality. The glass building is supposedly capable of leaving architectural representation behind. The recent wave of construction of court buildings in the Netherlands has produced exactly those glass boxes. Examples include the International Court of Justice and the Supreme Court in The Hague, and the design for the new district court in Amsterdam. My sketch of the history of the Supreme Court in The Hague caused excitement in Einsiedeln.

The first building for the Supreme Court, designed by architect Willem Rose, was completed on Plein in 1860. The building had a wide exterior staircase leading to a central entrance with a timpanon. It was extensively remodeled in 1938 by architect Gustav Bremer. The tympanum disappeared. However, Bremer monumentalized the exterior staircase by adding six bronze statues of Dutch scholars of law. The position of the statues followed the geometry of the facade. Visitors would climb in between the scholarly authorities. In 1988, the Supreme Court on Plein had to make way for the expansion of the Dutch parliament. The new accommodation was designed by architect Peter Pennink. That building differed in little from an average municipal library of the time. The bronze legal scholars, saved from demolition, were placed on either side of a tiny front door in the front yard.

In 2016, the Supreme Court got once again a new home. The excitement in Einsiedeln had less to do with the idiom of this totally glazed Supreme Court than with the constant dragging of one of the most important institutions of the Dutch rule of law. The building failed to anchor itself in the city of The Hague after Bremer’s interventions, for example through the representation of legal history and the long-standing connection of the bronze jurists to the building.

What aroused abhorrence besides surprise was that the Dutch State does not even own the building and shows no ambition to house the Supreme Court sustainably. The building, including energy bills, lunch snacks, erasers and toilet rolls, is leased from a construction company. The so-called Design, Build, Finance, Maintain and Operate (DBFMO) contract has been secured for a period of 30 years. Within the tender procedure followed, the glass architecture can hardly be questioned. An icon was demanded and we got what we deserved: craftsmanship. Again, the justices were moved with it. Unmoved, they stand like passers-by on the sidewalk of Korte Voorhout, ready to be hoisted up to a new home that can meet the whims of the future age. For the lobby, invisible from the street, another work of art has been commissioned – Helen Verhoeven’s otherwise beautiful mural.

How can this state of affairs be understood? Does the Supreme Court building represent a new degree zero in the representational capacity of architecture, and have we said goodbye to any pursuit of intelligible civic architecture? Or are we in the Netherlands just too indifferent to talk about such things? Do we settle for bronze legal scholars who are constantly on the move?