Van der Vlugt, All-round Midfielder of the Interbellum

Book review Joris Molenaar, Brinkman en Van der Vlugt architecten, nai 010, Rotterdam 2012, published in: De Architect, 2013

In 1983, students Jeroen Geurst and Joris Molenaar published the book Van der Vlugt, architect 1894-1936 on the occasion of an exhibition at the architectural firm Van den Broek and Bakema. Joris Molenaar’s fascination with Van der Vlugt’s work continued in his later design practice. In 1988, he restored Huis De Bruyn, in 1998 Huis Sonneveld. At the same time, Molenaar worked on a varied new-build and restoration oeuvre that is deliberately not stylistically fixed. With Jan Willem Walraad, for instance, he carried out the restoration of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, designed by Ad van der Steur, a contemporary of Van der Vlugt.

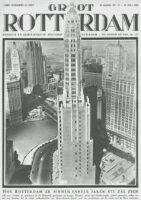

With the monograph Brinkman & Van der Vlugt Architects published this year, Molenaar is making an attempt to position the work of the firm in which Leen van der Vlugt participated within the architectural discourse of Rotterdam between the world wars. Whereas in port city Hamburg a monumental cityscape was enacted at the very same time, engineers like Rose, De Jongh and Burgdorfer built mainly on Rotterdam’s harbour, infrastructure and hygienic water management. This functional Rotterdam had a shaky relationship with the historic city. As now, Rotterdam saw a mass urban exodus of better-off people to coastal towns like Wassenaar. Young entrepreneurs like Plate, Van der Mandele and Van der Leeuw supported the modernisation of the city. With the appointment of city urban planner Willem Witteveen and city architect Ad van der Steur, work began in the 1920s to realise a Rotterdam City ideal. City planning became an extension of the urban imagery.

With the monograph Brinkman & Van der Vlugt Architects published this year, Molenaar is making an attempt to position the work of the firm in which Leen van der Vlugt participated within the architectural discourse of Rotterdam between the world wars. Whereas in port city Hamburg a monumental cityscape was enacted at the very same time, engineers like Rose, De Jongh and Burgdorfer built mainly on Rotterdam’s harbour, infrastructure and hygienic water management. This functional Rotterdam had a shaky relationship with the historic city. As now, Rotterdam saw a mass urban exodus of better-off people to coastal towns like Wassenaar. Young entrepreneurs like Plate, Van der Mandele and Van der Leeuw supported the modernisation of the city. With the appointment of city urban planner Willem Witteveen and city architect Ad van der Steur, work began in the 1920s to realise a Rotterdam City ideal. City planning became an extension of the urban imagery.

Witteveen advocated a monumental modern city of streets, squares and canals bordered by solid brick buildings. The schools, municipal buildings and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen that Van der Steur designed can be considered the architectural complement to the City ideal. The white international architecture, which Brinkman & Van der Vlugt became known for, was not at odds with this City ideal, according to Molenaar. The exceptional position assigned to white architecture in the cityscape was allegedly a deliberate strategy. The Bergpolder flat designed with Willem van Tijen was acceptable as a freestanding high-rise on a site lined by brick building blocks. Conversely, the urban design work of Brinkman & Van der Vlugt points to a principle reciprocal relationship between urban design and architectural image that is closely related to the deployment of the City ideal in the interwar period.

By interpreting this context, the image of Van der Vlugt as the goalgetter of the vanguard functionalist squad evaporates. Molenaar portrays him as an all-round midfielder in the football pitch that was shaped by the city in which he worked, his office and the commissioning world. Apart from the white masterpieces, he presents, for instance, the façade designs for the street walls in Bospolder Tussendijken. This involved limited urban planning directives on the architectural task. Both the various Brinkman and Van der Vlugt generations developed brick façades for houses and shops for various kinds of developers and investors without interfering with the floor plans. In this way, Mathenesserlaan, for example, became a coherent architectural piece of urbanism. Molenaar presents the Rotterdam City ideal as a form of total football. Like a true football manager, Witteveen enabled Messrs Brinkman and Van der Vlugt to shine only on occasion.

In the presentation of the projects, historical visual material has been supplemented with drawn reconstructions by the author. Where possible, Jannes Linders photographed the buildings in their current state and their changed urban environment. The book is written with a keen eye for the context of commissioning structures and urban policy. In that respect, this monograph is akin to Jean-Louis Cohen’s recent standard work The Future of Architecture since 1889. In this book, too, issues of politics, international exchange of ideas and local roots determine the perspective on architecture. Unmistakably, Joris Molenaar adds his experience as a practitioner of new construction and restoration.