The Detail Does not Exist

Published as postscript to: Marjolein van Eig, Het Detail, De Architect 2021, with an introduction by Merel Pit & essays by Violette Schönberger & Mark Pimlott

In the Renaissance, there were no guilds for architects. The project for a building, to avoid the word design, did not assume the complete mastery of construction. The foundations, the coarse and fine brick structures, plastering, stone and carpentry work were done by members of different guilds. The guilds, and not the architects, guaranteed the construction quality. The coordination of construction was also a financial affair, carried out by insignificant officials. Long before builders and architects made their appearance, craftsmen and construction managers regulated the fortunes of the site.

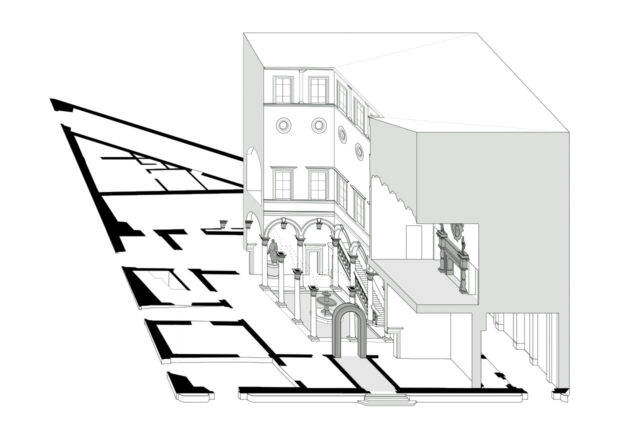

In Florence stands the Palazzo Gondi, built to a design by Giuliano da Sangallo, a member of the sculptors’ guild. As a designer, Sangallo was condemned to authority without mandate. According to the culture of the time, he arranged the irregular building plot in a divine geometric system of axes. It defined the location of the portone (front door), the androne (front hall), the cortile (court) and the scala (external staircase to the living quarters). Windows and doors reflect the geometry by their position centrally between the axes. Stonemasons probably designed the rusticated panels, the window and cornice frames and the facade cladding, which becomes finer on each floor, with or without disputes with the artist Sangallo. In the façade, diamond-shaped natural stone slabs mark the axis lines. The result is just about good, but refined.

With his limited mandate, Sangallo established the most stable qualities of the palazzo: the type, the geometry, the materials. He himself shaped only a few key moments in the routing to the main living area. He made the balusters of the scala, the column capitals in the cortile and the huge fireplace on the piano nobile. Palazzo Gondi, a prominent building in the architectural renaissance canon, possesses neither an architect nor details.

The divine system of axes ensure that the constituent parts of Palazzo Gondi remain related. At the same time, within each fragment a different one can be found. From a distance, the natural stone rustica appears to be a mere ‘texture’. Closer up, chisel marks, joints and the reflective mineral aggregate articulate the material of the rustica.

It could be a liberating observation that architecture does not prove itself in the details of fragile fencing, sensitive colour schemes, invisible fixings and the choice of the right taps, building hardware, sensible light fittings and other designer accessories. ‘God is in the details’, the modernist Ludwig Mies van der Rohe would state later. In the Renaissance, however, God did not reveal himself in spectacular architectural structural details. The mystification of the detail, the accompanying can do of the architect and -not to be forgotten- the illusion of integral micromanagement by the Building Information Model are recent phenomena that conceal the fact that the designers’ mandate is limited. It has never been otherwise.

The detail exists as the atom exists. With great difficulty one can talk and calculate about it and yet the indivisibility is apparent. New elementary particles are constantly appearing. They fall apart ever faster and maintain ever more mysterious relationships with each other. The relationship with reality is unstable. The detail enhances building management and architectural education. Rarely is the detail the subject of professional criticism. That is the importance of this collection of reports from practice by architect Marjolein van Eig.