Machine à Amuser

Book review Wim van den Bergh, Machine à Amuser, The Life and Death of the Beistegui Penthouse Apartment, published in De Architect 2024

1931 saw the completion of the Le Corbusier-designed Villa Savoye in Poissy and Carlos de Beistegui’s penthouse in Paris. At first glance, these buildings have little in common. The flirtation with concrete technology in Villa Savoye, for instance, is absent in the penthouse. In Villa Savoye, long ramps run from the front door over a first-floor patio to the toit jardin (roof garden). It is a ceremonial climb. As such, the Villa Savoye was not intended as a residence, but served as a backdrop for photos and parties – and for photos of parties in the Paris suburb. In contrast, the design for the Beistegui explored the urban variant of the toit jardin. After the hype of penthouse living swept over from New York, Parisian city lofts had been discovered as hip living spaces. The penthouse was located on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, around the corner from the Arc de Triomph. Visitors did not have to undergo ceremonies on the stairs and were dropped off at the front door by a lift. However, it was as much of a showpiece as the Villa Savoye.

1931 saw the completion of the Le Corbusier-designed Villa Savoye in Poissy and Carlos de Beistegui’s penthouse in Paris. At first glance, these buildings have little in common. The flirtation with concrete technology in Villa Savoye, for instance, is absent in the penthouse. In Villa Savoye, long ramps run from the front door over a first-floor patio to the toit jardin (roof garden). It is a ceremonial climb. As such, the Villa Savoye was not intended as a residence, but served as a backdrop for photos and parties – and for photos of parties in the Paris suburb. In contrast, the design for the Beistegui explored the urban variant of the toit jardin. After the hype of penthouse living swept over from New York, Parisian city lofts had been discovered as hip living spaces. The penthouse was located on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, around the corner from the Arc de Triomph. Visitors did not have to undergo ceremonies on the stairs and were dropped off at the front door by a lift. However, it was as much of a showpiece as the Villa Savoye.

Much is known about design history of the Villa Savoye.i Wim van den Bergh has studied the genesis of de Beistegui’s penthouse for some 40 years and recently published the results in a weighty book.ii The author leaves historiography and cultural criticism for what they are. The book has a distinctly architectural character, for the design practice is its focus.

This is evident first of all from Van den Bergh’s descriptions of the erratic, and sometimes grim, dynamic between the client and his contractor, two vain cultural entrepreneurs who were up against each other. The 31-year-old wealthy playboy de Beistegui moved in aristocratic circles, in which he wished to present himself as a patron of the surrealist avant-garde. He organised a series of job interviews, in which, apart from Le Corbusier, Gabriel Guevrekian and André Lurçat, all CIAM members, participated. He picked the least pronounced design, probably because it was the one that could best be moulded to his liking and Le Corbusier would bring the most prestige. De Beistegui felt free to give his architect a variety of instructions, which he sometimes borrowed from the – unpaid – designs of his competitors. While the professional Le Corbusier slapped his principal around with urban planning regulations that limited the expansion of the penthouse, de Beistegui hit back by constantly incorporating new gadgets, including a periscope overlooking the Parisian horizon, into the design.

Subsequently, extensive archival research of both men’s sketches and drawings feed the narrative. With the backing of correspondence between de Beistegui and Le Corbusier, Van den Bergh succeeds in reconstructing the design history.

In doing so, the drawing constitutes Van den Bergh’s own medium in addition to an object of study. The book contains minute reconstructions of Guevrekian’s and Lurçat’s designs and Corb’s seven plan stages. Van den Bergh’s digital line drawings possess the gloss of objectivity, but of course they are interpretations, mostly the outcome of comparing and combining chunks of information from the archive. As a practising architect, Van den Bergh takes liberties no longer admissible in the academic world of architecture.

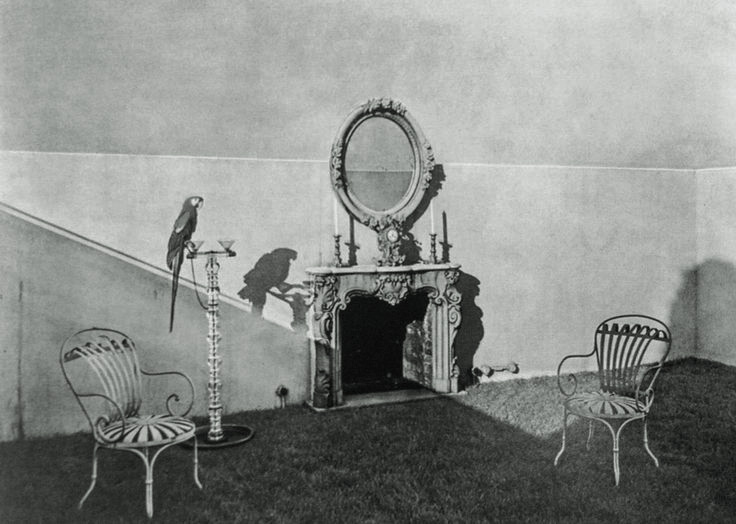

And finally, Van den Bergh demonstrates how the urban version of the toit jardin took shape through a series of different roof gardens. The highest garden had a grass lawn and was walled. The famous photograph showing an antique mantelpiece with the silhouette of the Arc de Triomph behind the wall was taken there.

After completion, it emerged that de Beistegui had used his architect, according to Van den Bergh, merely ‘as a technician hired to set a stage that would be completed by his wealthy socialite client.’ De Beistegui took up the fitting out with some friends. His ecstatic ‘entertainment machine’ would feature extensively in international lifestyle magazines.

After World War II, de Beistegui got bored with his toy. The penthouse fell into dilapidation. With his study, Van den Bergh saved it from oblivion. However, the book’s significance extends further. Van den Bergh rewrites the lifestyle and the architectural as one history. He writes about the rooftop patio: ‘Take away the fittings – the metal chairs, ornate mantelpiece, and mirror – and the space is merely a void. Once installed, however, these elements transform one’s perception of the space: the lawn becomes a lush flowering carpet, and the white perimeter becomes a wall that meets a ceiling of sky. It is only through the insertion of these decorative pieces that the architecture itself becomes clear.’

With compassion, Van den Bergh deals with the egos of Le Corbusier and de Beistegui. By taking seriously the connection of architecture and task definition, its genesis and use, Van den Bergh clarifies the role and character of the design profession.

Wim van den Bergh, Machine à Amuser, The Life and Death of the Beistegui Penthouse Apartment, MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 2025, ISBN 9780262048774

i In The Netherlands mainly because of: Max Risselada, Raumplan versus Plan Libre: Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier, 1919-1930, Delft 1988

ii Previously appeared: Wim van den Bergh, Beistegui avant Le Corbusier, Genèse du penthouse des Champs-Élysées, Paris 2015