Lutherhof, a Dutch Palazzo for Living

Published in: Binnenstad #312, 2023

On Staringplein in Amsterdam, architect Dirk van Oort (1862-1933) realised the Lutherhof housing estate in 1909. Clearly Van Oort knew his classics: the work of Berlage and Cuypers, but the free-style of the Amsterdam School was already presenting itself. However, the style is not what makes the Lutherhof pertinent. In designing Lutherhof, Van Oort displayed his knowledge of typology, in this case the typology of the residential palazzo. As a proven alternative to high-rise and high-density construction, its urban quality is topical.

On Staringplein in Amsterdam, architect Dirk van Oort (1862-1933) realised the Lutherhof housing estate in 1909. Clearly Van Oort knew his classics: the work of Berlage and Cuypers, but the free-style of the Amsterdam School was already presenting itself. However, the style is not what makes the Lutherhof pertinent. In designing Lutherhof, Van Oort displayed his knowledge of typology, in this case the typology of the residential palazzo. As a proven alternative to high-rise and high-density construction, its urban quality is topical.

Some scholars still reduce the current architectural debate to the battle between the modernists and their opponents. Vincent van Rossem wrote in this magazine that students at TU in Delft are taught to embrace modernism. However, that is no longer the dominant scope in architecture. Although it is totally unclear what the paradigms are now, the realisation that modernism offers a limited canon has now penetrated Delft and other architecture schools. But that is less important than the problem underlying this. The stylistic approach to architecture reduces buildings to their appearance. Even the current image and experience culture narrows the architectural debate back to a discussion of style, which began in the nineteenth century when design, theory and history became increasingly separate domains within architecture.

The history of the palazzo type illustrates this issue. Around 1909, the palazzo was a well-known Dutch phenomenon. Newly qualified architects like W.M. Dudok, A. van der Steur jr. and H.P. Berlage completed their studies by taking a Grand Tour of Italy. They took the palazzo type back with them to use it in institutional architecture, successively in the Hilversum town hall, the Museum Boijmans in Rotterdam and the Municipal Museum in The Hague (now Kunstmuseum Den Haag). As in everyday parlance, palazzo in architectural jargon refers to imposing accommodation for the elite – not mass housing.

Little is known about Van Oort.1 Overlooking the design for Lutherhof, however, he must have studied the palazzo type well. Lutherhof follows the simple set-up of the palazzo with a building mass enclosing an atrium. Unlike the villa, it is definitely an introverted type. And unlike the conventional terraced house, the palazzo does not lend itself to mass production.

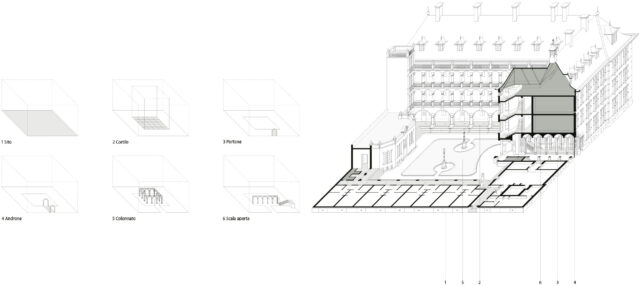

Palazzo typology

Typology, understood here in the literal sense of the knowledge of type, leaves style and appearance for what they are. Sometimes this geometry contrasts with the shape of the building plot, but always its location and format are imperative in the spatial and functional organisation of the palazzo. Square grids form the substrate for the placement of columns, which in turn form arcades. The ‘scala aperta’ or external staircase, starts from the collective atrium. This is not just any staircase; it has a more or less ceremonial character. In the urban realm, the palazzo appears as a mass clearly larger than the row house. The entrance to the atrium is the ‘portone’, the gate. It is larger than the front door of a terraced house and underlines the collective status of the palazzo. Crucial in the spatial sequence from the street to the residential domain is the ‘androne’: the reception room, which lies between the portone and the atrium. This is an independent space, often emphasised by a vaulted ceiling and by piers or an arch separating the reception and the atrium. Often the androne has doors leading to dwellings, a subsidiary spaces or an administrator’s room. The palazzo evolved into the speculative residential palazzo after the Renaissance.

Thus, residential palazzos established the typological building blocks of Naples’ growth in the eighteenth century. The scala aperta evolved from a laterally situated stately staircase to the ‘piano nobile’ of the urban elite to an opulent stairwell at the rear of the atrium. The scala aperta autonomised itself into a three-dimensional object.2

In contrast, the arcade lost its significance as a waiting and display area and is at best rudimentarily present in Naples. The eighteenth-century palazzi San Felice (design Sebastiano Felice, 1726), Mastelloni and Costantino (both designed by Nicola Tagliacozzi Canale, mid-eighteenth century) are well-known examples.

Lutherhof

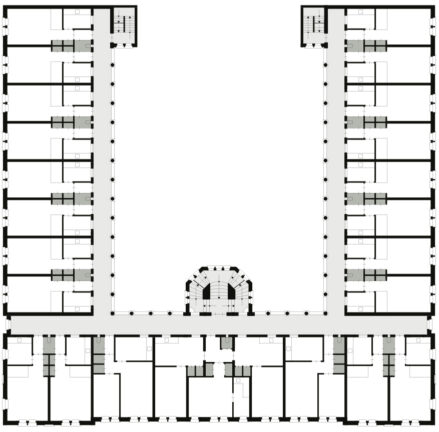

Lutherhof is located at the head of a closed perimeter building block. Van Oort translated the palazzo repertoire into the task of housing for single women. The floor plan is U-shaped. The main entrance is on the axis of symmetry at Staringplein. The design is premised on an atrium, which Van Oort not only used to provide access to the dwellings, but – more importantly – developed into the focal point of everyday living in his hands. The atrium has the residual size that results when the housing depth is subtracted from the plot size. Regular rows of columns define three colonnades that delineate the atrium, referencing the geometry of the Italian atrium. At the back of the atrium, the necessary escape stairs from the colonnades lead to a single-storey pavilion with bathrooms, storage space and even a corpse room. The front facade of the Lutherhof on Staringplein got a large portone, flanked on either side by two small doors.

Without a doubt, the androne and the scala aperta are the result of delicate design experiments. The gate and the two little doors lead into a zoning of one wide and two narrow spaces. Two rows of columns separate those spaces. Transverse to the androne lie the entrances to the administrators spaces and the boardroom. The scala aperta located at the end forms the threshold to the atrium. It is a complex staircase with two lateral flights leading to a single central flight on the symmetry axis of the building. Especially in the scala aperta, the building eschews stylistic references. As in Naples, but not exactly as there, the scala aperta is a self-contained object. The androne and the scala aperta are lyrical in spatial terms, but remain sober in materialisation. Following the 1909 insights, the walls are constructed with common bricks, in a regular bond, and then fitted with tiled panels and natural stone seats.

Sustainability

Lutherhof is proving to be perfectly adaptable. The flats for the single women were small and have in some cases been put together two by two. Lifts were installed in the dead-end parts of the colonnades and the attic was converted and made suitable for flats. The garden pavilion now serves as a bicycle shed and communal washroom. Today, Lutherhof is ‘gender-neutral’. Residents have taken possession of the colonnades by setting up seats, flowers and plants.

National Heritage Register

In the reality of the then construction culture, the typology of the palazzo was re-charged in the design. Just as the palazzo in Italy was given different expressions for each city and period, Van Oort deployed the type soberly and naturally. Especially in typological terms, therefore, it is a design that relates critically to the housing production of 1909 and beyond. In the Netherlands, the Lutherhof is the first and last distinct example of a residential palazzo. After its completion, architect Jan Gratama wrote a sympathetic critique of the design, which he incidentally categorised typologically as a ‘Dutch courtyard’.3

In 2002, the Lutherhof was listed in the National Heritage Register. Recently, Willemijn Wilms Floet published two design drawings of the Lutherhof in her dissertation as an example of a ‘courtyard plan typical of their time’.4 Otherwise, the building has hardly been noticed in the professional world and plays no role in the professional discussion. Unfortunate, because what would have happened if the housing canon had been receptive to more urban housing types than the terraced house, the gallery building and the tower block? How would architectural history have developped if not the Kiefhoek row housing, de Bergpolder tower block en de Victorieplein point block point block had been the typological measure of housing, but the lessons of exotic, complex residential palazzos like the Lutherhof had been taken to heart?

Notes

1 A start has been made in: Vincent van Rossem, Amsterdam 1900: Dirk van Oort (1862-1933), Binnenstad #240

2 Dirk De Meyer, Showpiece and Utility, Eighteenth-century Neapolitan Staircases; Ghent 2017 & Dirk De Meyer, Show- piece and Utility, More EighteFenth-century Neapolitan Staircases, Ghent 2018

3 J. Gratama, Een diaconiehof te Amsterdam in: Bouwkunst, 1910, p. 1-16

4 W. Wilms Floet, Het hofje, Bouwsteen van de Hollandse stad 1400-2000, Nijmegen 2016, p. 125