The Lecture of the Stonborough House

Published as: Hans van der Heijden, Literature and architecture: against optimism, The Reader #36, 2009

When we build, we also talk and write, Ludwig Wittgenstein asserted in his Philosophical Investigations. He could know. Wittgenstein designed one of the key 20th century pieces of architecture, the house for his sister Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein. The aphorism reflects his later instrumental view on the use of language in which communication on practical matters is measured by its effectiveness and not by linguistic logic as formulated earlier in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. But in the context of Wittgenstein’s Vienna the aphorism is more ambiguous than that. It also reads as a plea for a reciprocity between the art of architecture and that of the written and spoken word and as a plea to explain and justify the things we do at length. Ludwig Wittgenstein was a moralist. He was also a radical dilettante in many fields. He worked as a mechanical engineer, a soldier, an architect, a village teacher in Trattenbach and a professor in philosophy in Cambridge, but perhaps his real passion was music.

When we build, we also talk and write, Ludwig Wittgenstein asserted in his Philosophical Investigations. He could know. Wittgenstein designed one of the key 20th century pieces of architecture, the house for his sister Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein. The aphorism reflects his later instrumental view on the use of language in which communication on practical matters is measured by its effectiveness and not by linguistic logic as formulated earlier in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. But in the context of Wittgenstein’s Vienna the aphorism is more ambiguous than that. It also reads as a plea for a reciprocity between the art of architecture and that of the written and spoken word and as a plea to explain and justify the things we do at length. Ludwig Wittgenstein was a moralist. He was also a radical dilettante in many fields. He worked as a mechanical engineer, a soldier, an architect, a village teacher in Trattenbach and a professor in philosophy in Cambridge, but perhaps his real passion was music.

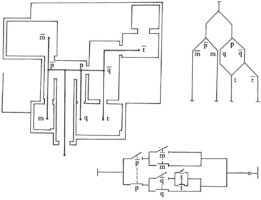

A lot has been said and done to interpret the virtuosity of the Stonborough House that was designed in 1926. Architectural theorists have tried to read its floor plans as logical diagrams, as architectural switchboards so to speak, others have stressed the ethical values of the elementary volumes and bare aesthetic or the maniacal craftsmanship of its details. However, there is also evidence that the Stonborough House was a place of nostalgia. It was full of melancholy and memories.

The spatial arrangement of the house roots in the domestics conventions of the Viennese aristocracy of the time. The living rooms of the house are on the first floor. It is an urban Palais with a stately route from the entrance vestibule to the upper floor. Double glass doors in the vestibule give way to a straight staircase running to the upper lobby. The eye is focussed on a piece of sculpture positioned in the axis of symmetry of the stair. The house refers to the particulars of the Wittgenstein family tradition in very explicit ways. The sequence of the vestibule doors, staircase and statue is literally taken from the Palais of Karl Wittgenstein, the father of Ludwig and Margarethe. In both houses the Saal (drawing room) is important as a place to for reception and music performance. Karl Wittgenstein had a reputation as a supporter of musical talent and music was a driving force in his family.

In the Stonborough House these domestic rituals have radically been intensified by reducing the formal vocabulary of the architecture. Unlike the almost baroque precedent of the father’s house, the Stonborough House is Spartan in appearance. Decorations and expressive finishing such as carpets, floor and wall paintings are absent, thus reinforcing prime architectural choices: the spatial sequence along the axis of symmetry of the lobby and the dominance of the statue in the route leading upstairs.

In all senses of the word the Saal is a pivotal space in the Stonborough House. Contrary to the staircase, the Saal does not refer to a specific pre-existing room, but is carefully manipulated within the space plan of the house and accurately positioned between the lobby and the private rooms of Margarethe.

Another Wittgenstein sister, Hermine, has extensively drawn both her father’s and her sister’s house. A meticulous ink drawing shows the staircase with the statue of her father’s house. By comparison, the interior of the Stonborough House is rendered far less precise and more spherical, using charcoal in most cases. The drawings show how the house was occupied in a slightly disorderly fashion. It does not lose its Spartanism altogether, but it is also not depicted as a grandiose piece of total design. It does not show as a consistent modernist house in the sense that it contained stylish contemporary furniture and art. Today, we might even be tempted to describe the furnishing is incorrect: the house appears to be strongly personalised. Mahogany tables, crapauds, porcelain, candles, and art on pedestals lend the spaces a considerable degree of intimacy (but not cosiness, the light comes from bare light bulbs). This is confirmed by the photographic snapshots Ludwig Wittgenstein glued in his notebooks. The house must have been a bohemian place where Viennese intellectuals gathered, drank coffee and Schnapps. The polish of antique grand pianos and cellos would not have looked odd. It was a home, the home of the family of Ludwig’s sister Margarethe.

The Spartan properties of the architecture are reductive in nature much rather than abstract. That is an important distinction. Wittgenstein’s design does not rework traditional motifs with the objective to arrive at a new vocabulary. The Stonborough House is not revolutionary. It is an open question whether its Spartanism is more or less intimidating than the baroque of the father’s house, but what is important is the intention to approach architecture as an art that is rooted in traditions small and large. Hermine Wittgenstein’s drawings and the photographs avoid to describe any architectural purity and focus on the habits and rituals of the family.

These habits and rituals, by the way, were problematic. Father Karl Wittgenstein was a dominant man, his expectations of the children were high, three of his sons committed suicide, music in the house represented culture, and was practised as a top sport in which it was not easy to earn praise. Wittgenstein family life was tragic. Difficult as it was, the reference in the design to the family’s history was a firm token of realism. Much later, in 1946, Ludwig Wittgenstein would write: ´Tradition is not something that everyone can pick up, it is not a thread, that someone can pick up, if and when he pleases; any more than you can choose your own ancestors. Someone who has no tradition and would like to have it, is like an unhappy lover.´

Compare the building, talking and writing of the Stonborough House to the architectural discourse today! Originality and innovation are now the criteria to judge architecture. Architects are supposed to have their own personal theory and style. The inherit contradiction is only clear to those who stick to the notion that theories and styles are shared intellectual properties. It is as if such theoretical anxiety must compensate for the lack of a significant agenda for architects. The literary vehicles that are used in architecture are descriptive in nature and style (minutes, specifications, tables, schedules) or testimonial (critiques, design statements) and only rarely investigative (mostly in an academic context) and the overall tone is likely to be ostentatiously positive. Architecture is forced into a performative corner. Architectural space seems to be possessed by a merciless optimism in which there is little room for doubts and complexity. Inevitably design visuals are supplied with clean streets, mothers with prams and roller-skating kids. It never rains in these architectural utopias. Doubts, complexity and melancholy don’t solve problems and certainly don’t sell in the anonymous markets in which design functions today. Good cheer does. Ambiguity is out.

We do not live in revolutionary times. Our built environment is complex, expanding and in constant flux. Literature is much better equipped than any architectural analysis to interpret these dynamics. Words make us aware that our built environment this is not just a physical world, but also a lived world. Wittgenstein suggested that the dignity of a habitat relates to the habits and rituals of its occupiers. Viewed in his way, a home or a habitat is not only a backdrop for pleasure and happiness, but also for disappointment, grieve and pain. The architecture of a house should not make a funeral look ridiculous. Our habitat is measured by such dramas and by the melancholy of life. Crucial of course in the case of the Stonborough House was the small gap that existed between the conception and consummation of architecture and that the architect Wittgenstein chose to associate himself quite strongly with the family life that eventually would take place in the house.

Architecture has its own professional tools and in that sense it is an autonomous artistic discipline. Yet, architecture as such changes little: Wittgenstein seemed to say that the value of architecture all depends on the engagement of its designers with the tasks they are given. Building by talking and writing as Wittgenstein did, helps architecture not to lose itself in innovation and utopia, but to develop as an ability to cope with reality instead- for better or worse. Paradoxically, Wittgenstein’s melancholic outlook on architectural issues should make us happier. ´The happy lover & the unhappy lover both have their particular pathos. But it is harder to bear yourself well as an unhappy lover than as a happy one,´ Wittgenstein concluded his 1946 aphorism on the inevitability of the traditions we build on.