Dwelling

Published as Carpenters Eye-column on: website Architectenweb, 2018

Affordable housing is back on the political agenda, but at the same time is rarely the subject of a substantive architectural discourse. Architects complain (as only architects can complain) about lost authority, about being sidelined by the initiative that market parties have taken in the design and realisation of such housing. How can the architecture of housing be studied in this context? Apparently, there is no such thing as a standard practice that designers can emulate.

Affordable housing is back on the political agenda, but at the same time is rarely the subject of a substantive architectural discourse. Architects complain (as only architects can complain) about lost authority, about being sidelined by the initiative that market parties have taken in the design and realisation of such housing. How can the architecture of housing be studied in this context? Apparently, there is no such thing as a standard practice that designers can emulate.

The ever-growing mountain of typology books offers exotic alternatives. Such books may be brimming with projects with complicated cross-sections and floor plans. Thus do they wrongly suggest an architectural can-do in the residential domain without clarifying how their extreme positions relate to economy of construction, the building process and dwelling itself. Without these insights, the experiments for the middle classes in Siedlung Halen in Bern and the Unité d’ Habitation in Marseille are incomprehensible and useless – and the view of necessary innovations in the here and now is obscured.

More relevant is the typological research of the Swiss architects Emanuel Christ and Christoph Gantenbein. In their typology books, they show local housing types that manifest themselves in cities such as Hong Kong, Rome, New York and Buenos Aires. They show how they arise from local particularism. The exotic nature of the cities and of living there is made understandable. Even the extreme examples they analyse usually have a rather banal origin. Studying them is instructive and useful in modern housing practice.

More relevant is the typological research of the Swiss architects Emanuel Christ and Christoph Gantenbein. In their typology books, they show local housing types that manifest themselves in cities such as Hong Kong, Rome, New York and Buenos Aires. They show how they arise from local particularism. The exotic nature of the cities and of living there is made understandable. Even the extreme examples they analyse usually have a rather banal origin. Studying them is instructive and useful in modern housing practice.

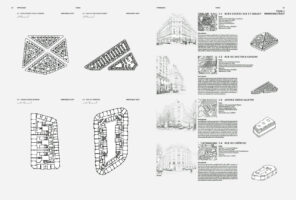

A further interesting phenomenon is the Neapolitan residential palazzo, built in large numbers from the beginning of the eighteenth century. The vitality of this speculative residential building is astonishing. It is the city’s mainstay housing type, derived from the palazzi built during the Renaissance in northern Italy. In Naples, the originally aristocratic type was simplified and made suitable for mass housing as a speculative project. There are usually several flats around a closed courtyard.

The Neapolitan palazzo is built with rough carpentry and masonry techniques. The decorations are done in fine stucco. In those days, building it was second nature. A specific peculiarity is the double staircases, usually situated at the back wall of the courtyard. From the gate (portone), intermediate space (cortone) and court (cortile), the staircase slowly emerges as a large piece of furniture. The spatial developments and their accompanying lyrical decoration stretch the essentially Classical architecture with architectural dissonances and counterpoints. It was the time of Baroque music, after all, of J S Bach and Antonio Vivaldi.

In other words: whereas in the Renaissance the court was fixed as a static and horizontally oriented living space and the staircase was literally an aside, Baroque architecture offered scope to design a new phenomenon: the vertical dynamism of the public staircase in the court.

Despite all these ceremonial qualities, the inner world of these palazzi is part of everyday life. The buildings are not all equally successful, are rarely neat and never serene. But often enough the staircases are full of lush plants; in the cortone, prams stand between the mailboxes and news-stands; bicycles and scooters are parked between the staircases. On a field trip my students met Maria, who let us in and showed us something of Neapolitan living.

Back home, the students continued to analyse the phenomenon and designed a modern palazzo themselves. We talked about architecture, certainly. But Maria’s virtual presence became compelling. The students did not feel detached from her culture and seemed to find it quite an honour to come up with decent house plans. They made coloured detail drawings of their own Neapolitan staircases. We talked about the architecture needed to make the reception area in an ordinary residential building find its form.

The enthusiasm that the palazzo phenomenon aroused in these young designers was infectious. The conclusion is obvious: thanks to Neapolitan typology, architecture was once able sustainability to define everyday living within the reality of commercial building and development.

There is another lesson. Because it could not be otherwise, Naples grew in the eighteenth century through compact, urban, medium-high-rise buildings. Neapolitan housing density is high and the city is vital. It demonstrates that there are alternatives to the typological repertoire, which all too often is limited to the terraced house, the stairwell and the residential tower. There really are other ways to densify cities.